January 4, 2026

Dr. Eric Chow

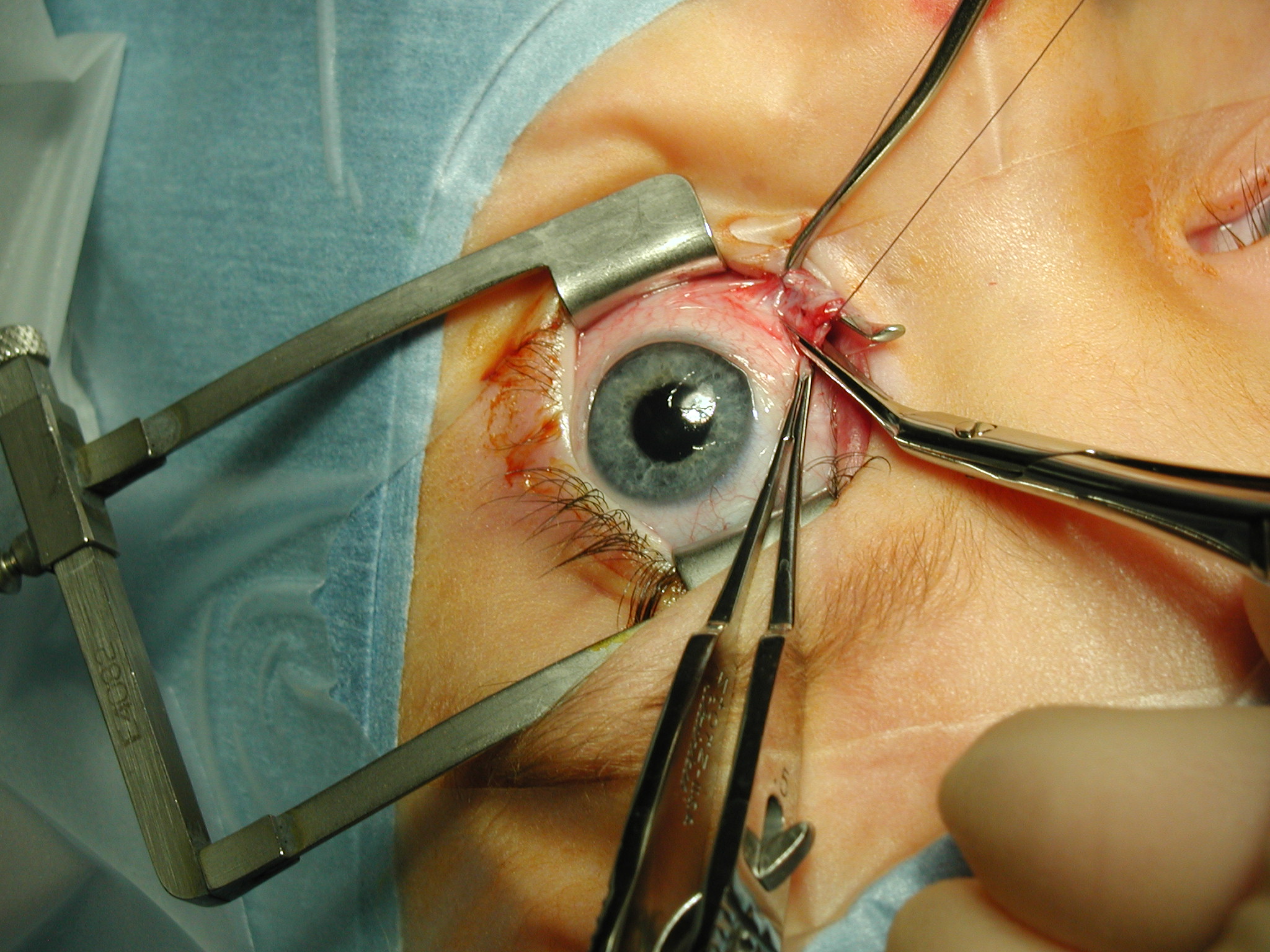

Surgery can help straighten the eyes—but that’s not the whole story. For people with strabismus (eye misalignment), the best results happen when eye surgeons and vision therapy optometrists work together.

Key Takeaways:

Strabismus surgery treats the motor side—realigning the eyes.

Vision therapy addresses the sensory side—teaching the brain how to use the eyes together and keep them aligned.

Collaboration between ophthalmology and optometry leads to better, longer-lasting results.

Without sensory rehab, even an initially well-aligned surgery can decompensate when the brain can’t keep up.

Strabismus isn’t just about eye appearance—it’s about how the eyes function together. The brain plays a huge role in that. If the brain hasn’t learned how to team the eyes properly, even a successful surgery can fall short. Patients may still see double. The eye may drift back. And often, additional surgeries are needed—not because the surgeon did a bad job, but because the brain never adapted to the eye’s new position in space.

This is where vision therapy comes in.

Vision therapy is like rehab for the visual system. It teaches the brain how to fuse images, how to control eye movements, and how to support depth perception—skills many strabismus patients never developed in childhood. And when therapy is done before and after surgery, outcomes are almost always more stable, comfortable, and effective.

In the most basic terms:

Strabismus surgery fixes the muscles.

Vision therapy fixes the brain.

Too often, we separate these as if they’re unrelated. But in reality, they’re two sides of the same coin. A muscle can be moved, but if the brain doesn’t know what to do with it, the benefits won’t last.

With better technology and a deeper understanding of how the brain and eyes develop together, it’s time for optometry and ophthalmology to stop working in silos. Both professions bring essential tools to the table. But when they stay in their own lanes, patients often lose out.

Take the vision therapy optometrist who never brings up surgery—even when the eye turn is over 25 prism diopters and clearly outside the range for therapy alone. Or the strabismus surgeon who dismisses vision therapy altogether, calling it expensive or ineffective without ever having seen it done well or understanding what vision therapy is. That kind of divide doesn’t help anyone. But when both sides talk, collaborate, and respect what the other brings? That’s when real, lasting benefits happen for our patients.

As someone who’s worked closely with both sides of this field, I’ve seen it firsthand. I’ve seen surgeries “fail” not because they were poorly done—but because the patient’s brain wasn’t prepared to support the new alignment. I’ve seen patients go through multiple corrective surgeries (up to 7!), when a few sessions of vision therapy—before and after—could have made the first one stick.

But either way, the idea is the same: prepare the brain before surgery, and then follow up afterward with a short round of post-op vision therapy to lock in the results. That’s how we give patients the best shot at long-term success—not just straight eyes, but eyes that truly work together.

If you or someone you love is considering strabismus surgery, ask this simple question:

“What are we doing to help the brain adapt to the eyes’ new alignment?”

Because it’s not just about how the eyes look—it’s about how they work. And that takes teamwork.

Surgeons and vision therapists don’t compete—we complete each other’s care.

It’s time to stop treating strabismus as a one-and-done procedure, and start treating it as a process. A well-coordinated, collaborative, and patient-centered process that combines the best of both professions. When we unite our expertise, our patients win. Every time.