November 18, 2025

Man Kin (Eric) Chow, OD, FAAO, FOVDR

Psychoeducational testing is designed to provide a deeper understanding of a child’s learning profile—how they process information, problem-solve, and perform across reading, writing, and math tasks. However, what if a child’s difficulty lies not in understanding the material, but in seeing the test accurately?

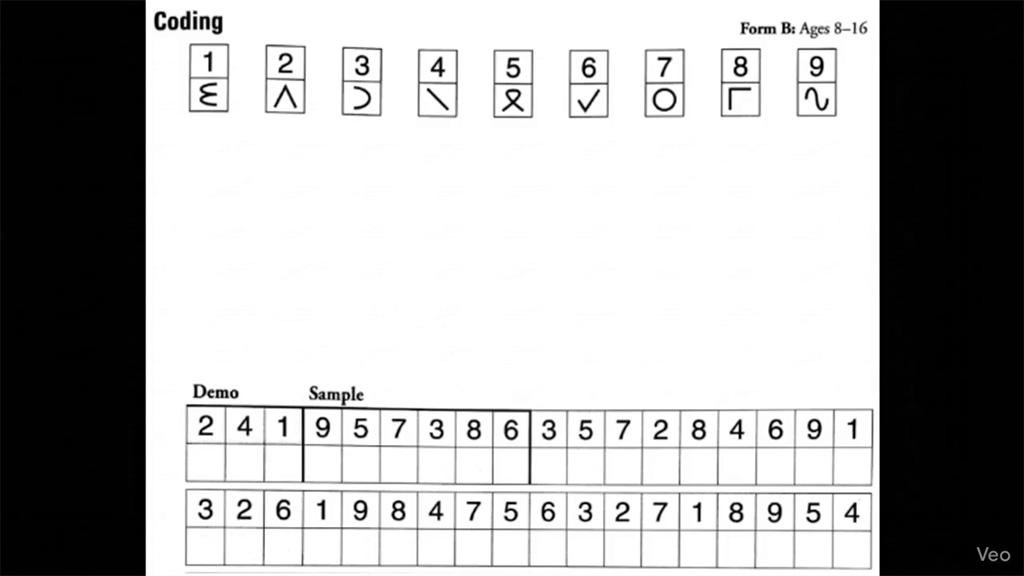

Many of the most widely administered assessments like WISC-V, NEPSY-2, Beery VMI, and TVPS-4, are visually demanding. They require children to scan, copy, decode, and manipulate visual information efficiently. When a child has undiagnosed visual challenges, such as tracking deficits, poor eye teaming, or delays in visual processing, the results may reflect these hidden obstacles rather than their true intellectual potential.

In this presentation, we will review sample pages from each of these tests to illustrate how children with visual difficulties perceive and experience them. We will break down how specific visual skills: accommodation (eye focusing), vergence (eye teaming), and oculomotor control (eye tracking) directly impact performance on psychoeducational assessments, while explaining these concepts in practical, easy-to-understand terms.

Recognizing and addressing these visual factors is crucial. When visual-spatial, visual-motor, or visual processing weaknesses are present, they should be identified and treated, ensuring that a child’s true cognitive abilities are accurately represented and supported.

This is what someone with oculomotor dysfunction may experience this page:

Oculomotor skills refer to the coordinated eye movements that allow a person to accurately track, fixate, and shift their gaze between targets, enabling clear and efficient visual processing. The include the following subskills:

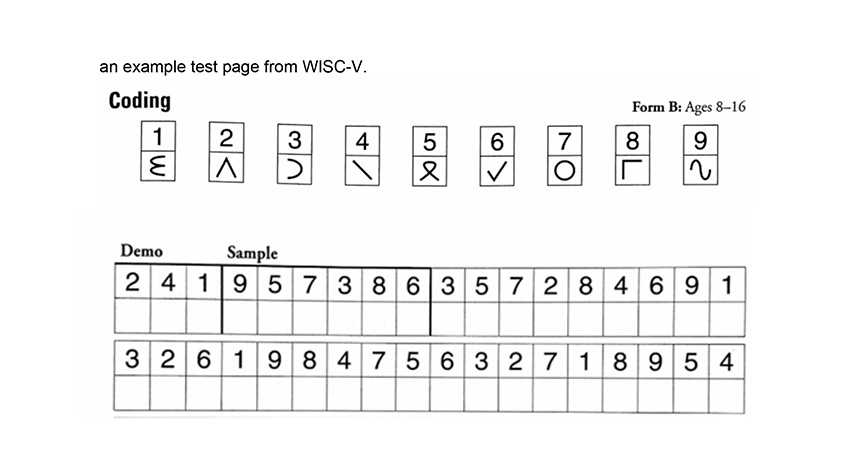

Here’s an example of a test page of NEPSY-2 Letter/Number Naming subtest. The purpose is to evaluate how efficiently a child can visually scan, recognize, and verbally name letters and numbers arranged in rows. It is primarily a measure of rapid automatic naming, processing speed, and visual scanning efficiency—skills that rely on smooth, coordinated eye movements and strong visual attention.

This is what someone with accommodation difficulties may experience

Accommodative skills refer to the eye’s ability to efficiently and accurately change, sustain, and relax focus when shifting between near and far objects, ensuring clear vision during activities like reading or looking from the board to a notebook. There are different type of accommodative issues:

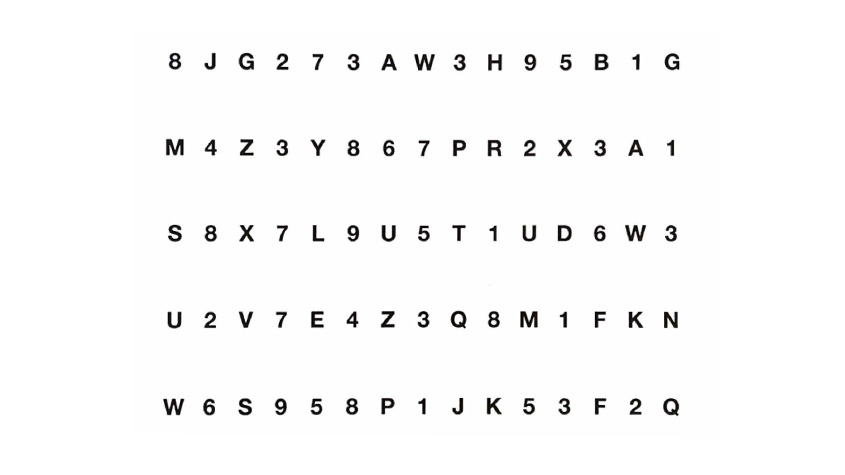

During the test, the child is shown a series of increasingly complex geometric shapes (starting with simple lines and progressing to intricate designs).

The child’s task is to copy each shape as accurately as possible in their test booklet.

The test includes three core components:

Here is an example of a test page from Beery VMI:

This is what someone with binocular or vergence difficulties experience

Vergence skills refer to the coordinated inward and outward movement of both eyes that allows them to align on a single point and maintain binocular vision and depth perception at various distances. There are different types of vergence issues:

A child with poor eye tracking, unstable fixation, or reduced visual-motor coordination may:

As an aside, many parents ask how vision can affect handwriting. Handwriting is a complex skill, involving fine motor coordination, spatial awareness, and visual-motor integration. From a developmental and functional optometry perspective, handwriting represents a motor output based on visual sensory input—if the information entering the visual system is inaccurate or inefficient, the written output will reflect that. As my mentor from SUNY College of Optometry, Dr. Rochelle Mozlin, used to say: “Garbage in, garbage out.”

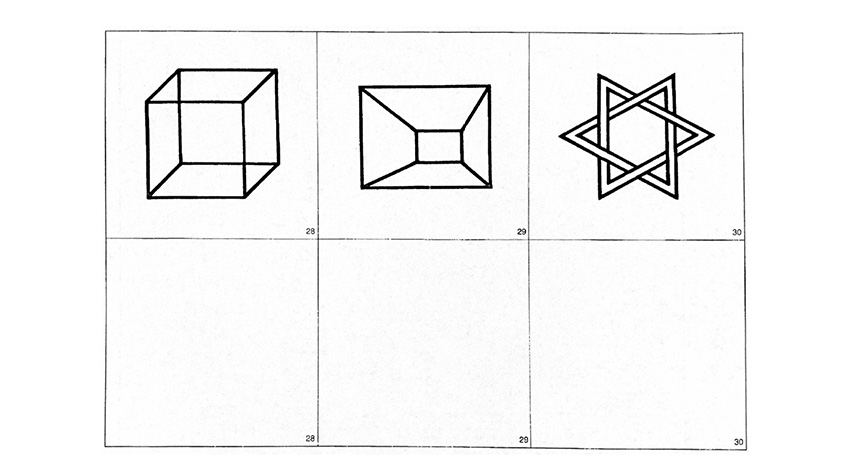

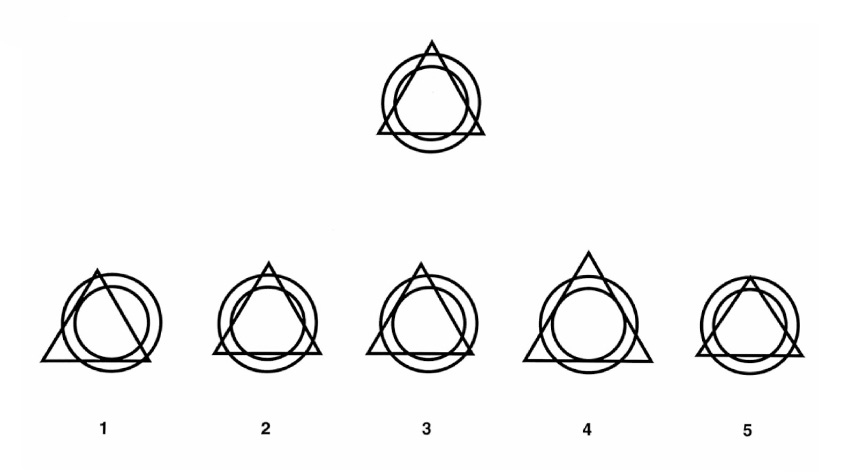

This is an example of a visual discrimination test part of the TVPS-4 test.

This is how a child with central peripheral vision integration issues see.

Central–peripheral integration refers to the brain’s ability to balance and coordinate focused central vision (used for detail and attention) with broad peripheral vision (used for spatial awareness and stability). When this system is imbalanced—often seen in individuals with autonomic nervous system dysregulation involving the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems—the visual system can become unstable. Patients may describe sensations of the world “zooming in or out,” feeling as though they are looking through a fishbowl, or that their surroundings appear compressed or expanded. This reflects a disruption in how the brain integrates visual information for orientation and depth perception. Instead of fluidly shifting between detailed focus and spatial awareness, the system oscillates or locks into one mode, leading to discomfort, disorientation, and visual distortion. Vision therapy in such cases aims to retrain the visual system’s balance between central and peripheral processing to restore a sense of visual stability and spatial grounding.

In summary, Imagine trying to solve a puzzle or read a passage while the image is unstable—moving, blurring, or doubling. Now imagine being timed while doing it. That’s the reality for many children with binocular vision dysfunction or visual processing issues. These children often show unexpected drops in performance, especially in timed tasks, multi-step instructions, or tasks that rely on copying or scanning.

It’s not that they don’t understand the material—it’s that the information isn’t being delivered to their brain in a usable way.

This distinction matters. A child’s testing results influence educational planning, diagnosis, and intervention decisions. If their visual system is not functioning efficiently, their scores may lead to incorrect labels or missed diagnoses. Worse, they may internalize these results as a reflection of their ability, when in fact their brain is working overtime to compensate for an unstable visual experience.

Psychoeducational results sometimes don’t align with the child’s classroom performance. When scores raise more questions than answers, visual efficiency should be on the radar. Consider referring for a functional vision evaluation if you observe:

A significant discrepancy between Verbal Comprehension and Processing Speed Index on the WISC-V

A normal Visual Perception score but a low Visual-Motor Integration score on the Beery VMI

Observations or complaints such as:

Headaches or eye strain during reading or homework

Words that blur, double, or appear to move on the page

Frequent line skipping, losing place, or finger tracking

Tilting the head or covering one eye while reading or copying

ADHD vs. Oculomotor Dysfunction: Visual tracking problems can reduce attention during reading tasks

Dysgraphia vs. Visual-Motor Delay: Poor handwriting may stem from eye-hand coordination deficits

Processing Speed Deficit vs. Accommodative Dysfunction: Visual focusing lag can slow down timed tasks

Identifying the correct source of the issue can prevent misdiagnosis and ensure the child receives targeted support.

Quick Screening Tools for Psychologists

You don’t need to diagnose visual problems to refer a child appropriately. These quick, in-office screens can help determine when further evaluation is needed:

Near Point of Convergence (NPC): Slowly move a pen or target toward the child’s nose. A normal response is single, clear vision until 2–3 inches away. Earlier blur, double vision, or drifting of one eye indicates potential convergence insufficiency.

Symptom Checklists: Brief tools like the CISS (Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Survey) can flag visual fatigue, discomfort, or avoidance of near work.

Oculomotor Screening Tools: Simple tests like the King-Devick or Developmental Eye Movement (DEM) Test can reveal tracking deficits. These assess saccadic eye movements during rapid number naming tasks and can help identify children struggling with visual attention or reading fluency.

What’s Next: Assess the System Before Measuring Performance

When conducting psychoeducational testing, it’s essential to consider how underlying visual factors may influence performance. This begins with evaluating—and when appropriate, addressing—visual efficiency and visual- processing. A comprehensive functional vision evaluation can uncover key areas of difficulty, including:

Addressing these deficits through vision therapy or appropriate interventions can help level the playing field, ensuring that psychological testing measures true cognitive function—not the side effects of a struggling visual system.